Four Habits to Help Kids with Social Anxiety

I wrote this article for the Greater Good Magazine on how social anxiety can show up in kids and what we can do to help.

Anjali sat at the kitchen table in front of a blank piece of paper. She sat, and sat, and sat. Then she got up from the table and walked away. The unfinished task? A Valentine’s card for her grandmother.

What was the problem? Eleven-year-old Anjali was the one who had decided to make a card, so the problem was not a lack of care. What was holding her back was a fear that her card would not be good enough for her grandma. Although she was seated alone at the table, she was experiencing social anxiety.

Social anxiety involves fear of negative evaluation, and this fear can stem from social interactions or performing in front of others. As Anjali pondered the creation of her card, she was imagining that her grandma would negatively judge her card and reject her.

Performance and social anxiety can be a natural part of growing up, but they can become problematic if children begin to avoid situations that trigger their fears or their fears become overwhelming. For youth, social anxiety disorder is often identified during the teenage years, and it includes anxiety related to interacting with peers. Often we hear about cases of teens who avoid going to school and interacting socially.

Other forms of social anxiety in children can include fears of being awkward in front of peers, fears of displeasing authority figures, fears of negative evaluation from others, preoccupation with siblings’ judgments, or an unwillingness to try tasks that don’t bring immediate success. Of course, experiencing anxiety about how others perceive you is a normal part of being human; it doesn’t necessarily mean that a child has an anxiety problem. What can make a difference in their life trajectory is not so much the presence or absence of these patterns, but rather how a caregiver helps a child respond to their fears.

Here are four habits that can help kids and parents effectively respond to anxiety-related symptoms before they reach the debilitating level of a disorder.

1. Notice and name your feelings, thoughts, and sensations

The journey to coping effectively with any mental or emotional challenge always begins with awareness. Kids who are experiencing social anxiety need to become aware of the emotions, thought patterns, and body sensations that accompany their anxiety.

To help kids identify feelings patterns, I like to use the Feelings Habit Animal Quiz that I developed. There are four feelings-related animal habits that many kids have: Bear explodes with feelings, beaver obsesses about feelings, chameleon hides feelings, and deer is ashamed of feelings. Most kids quickly relate to one or more of these feelings habits.

Playfully identifying with a feelings animal can help kids observe their habits with less judgment. It is common for kids with social anxiety symptoms to have the beaver habit of obsessing and the deer habit of feeling ashamed, but it’s important to remember that kids with anxiety are not always quiet and timid. Kids with anxiety can also hide feelings or be explosive with feelings. The key is to help kids non-judgmentally recognize and name their feelings habits. Naming our feelings can help to deactivate the alarm center of the brain, which can allow kids to think more clearly.

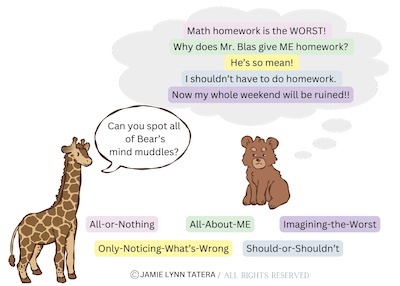

In addition to identifying feelings, it can also be helpful for kids to notice their thought patterns. It is common for kids with social anxiety problems to have a number of distorted thinking patterns that contribute to their anxiety. For this reason, one common treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can help kids identify these “cognitive distortions.”

When I teach kids about cognitive distortions, I call them “mind muddles.” Caregivers who would like to help kids informally learn about problematic thinking patterns could play a game of “pretend” with a child, imagining that a child’s favorite stuffed animal or toy is having big feelings and distorted thoughts. After listening to the stuffed toy’s thoughts, you could help the child to identify the mind muddles.

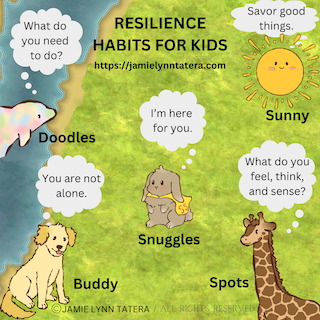

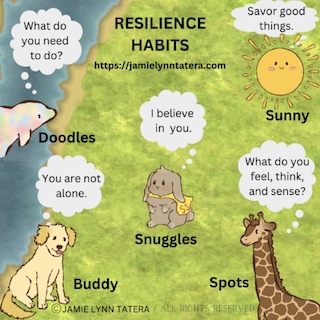

Just as I use a set of animals to talk about feelings, I use another set of animals to help kids learn resilience habits in both the Parent-Child Self-Compassion program that I’ve developed as well as the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbook for Kids series. Spots the giraffe is the resilience animal that can help us to “spot” our feelings, thoughts, five-senses and sensations. In this excerpt from the first Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbook, Spots invites us to “spot” Bear’s mind muddles:

Once children are adept at noticing and labeling the mind muddles of their stuffed animals, you can begin labeling your own mind muddles out loud, and then eventually help kids identify their own.

2. Understand that you are not alone

In a recent study (not yet published) of the Self-Compassion for Children and Caregivers program, the number-one resilience habit that kids reported using was the “Buddy habit.” Buddy the dog is the resilience habit animal that helps us to remember that we are not alone when we experience hard things. Children reported that the “Buddy habit” helped them with all kinds of difficult feelings:

“I find the Buddy habit really helpful, whereas before . . . I was like ‘I’m the only person going through this.’”

“The Buddy habit . . . taught me that everyone has feelings like this sometimes.”

Remembering that we are not alone can be especially helpful for kids dealing with social anxiety-related thoughts and feelings. Children with social anxiety are typically shame-prone and fearful of being negatively perceived by others. These children are often aware that their anxiety is not socially appropriate. Sometimes well-meaning adults tell kids that they “shouldn’t” feel anxious, but this just tends to compound kids’ anxiety and shame. What a child needs to hear instead is that other kids and grownups sometimes feel anxious, too. When an adult says, “Did I ever tell you about the time that I….” and shares about when they felt social anxiety, it creates a bridge to their child’s experience and helps the child internalize that they are not alone.

Caregivers can also expose their children to books in which the protagonists struggle with anxiety. Are You Mad at Me? is a delightful children’s book that tackles the topic of social anxiety in a playful way. When I left the book on a table in my living room, both of my daughters carefully read and reread the book. My younger daughter said, “What I love about it the most is that I can relate to it so much.”

JL Note: I interviewed the authors of Are You Mad at Me for my first, We Are in It Together podcast. You can view or listen to our podcast here, or wherever you like to listen to podcasts!

3. Soothe and encourage yourself with kindness

Self-compassion is an antidote to shame, and studies of adults and youth who have taken self-compassion training have found significant decreases in their anxiety symptoms. In a nutshell, self-compassion invites us to learn to treat ourselves with the same kindness that we would offer to a good friend.

When I teach children about self-compassion, I introduce Snuggles the bunny. Snuggles can soothe us with kind words when we are struggling. Reassuring words include, “You are not alone, I’m here for you, and I care about you.”

When Snuggles dons a cape, it’s Super Snuggles. Super Snuggles can help kids to do hard things, including facing their anxiety fears. Super Snuggles likes to say, “I believe in you. You can do hard things. You’ve got this.”

One parent-based treatment program, Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions (SPACE), teaches parents to provide their children with both validating and encouraging words. Children need to know that adults understand their struggles with anxiety-related feelings and thoughts. They also need to know that we believe that they can handle their anxious feelings and do hard things.

4. Take action and celebrate progress

Let’s return now to Anjali’s fear of creating a card for her grandmother. I know a little bit more about this story, because I happen to be Anjali’s mom. And because I’m a self-compassion-for-children teacher, I was able to help her identify and name her fear, and understand that she was not alone; and I offered her both gentle validation and strong encouragement. We talked about the pictures and words she wanted to create, and with some effort she created the cover of the card. But when it came time to write the interior, she again froze. Aren’t you glad that I chose an example that did not have an easy ending!?

In Anjali’s case, she needed extra support to complete the interior of the card. Her anxiety was preventing her from putting words on paper, but she was able to engage in conversation about what she might want to say to her grandma. I recorded her words on my phone, and then I replayed the words and sat with her as she wrote the words in the card.

After her grandma’s card was complete, we called Grandma, who squealed with delight as Anjali shared it with her. I encouraged Anjali to soak in the goodness of her grandmother’s joy. We then together retold the story of her anxiety and connected it to the joy that she brought her grandma by creating the card despite her fear.

Often kids with anxiety want to avoid events that trigger their fear, but avoidance only compounds their anxiety over time. This is why recommendations for social anxiety emphasize helping children move forward in the face of fear.

Supporting children when they have anxiety is critical, and it’s also important to progressively help children learn to face fears independently. In the parent-based treatment program, SPACE, parents are taught to gradually reduce their accommodations to help children learn that they can cope and move forward in anxiety-provoking situations on their own.

Coincidentally, as I was writing this article, Anjali decided to make a birthday card for a friend’s birthday. Within 10 minutes, she had independently gotten the paper, written a note, and decorated and colored the card. When I asked her how she had whipped through it so quickly, she mentioned that she had seen kids give a friend very imperfect birthday cards the previous week, which had reduced her fear and increased her trust in her friends’ acceptance.

Does this mean that Anjali will no longer suffer from shame-prone social anxiety? Absolutely not. This is a process that we will walk through together again and again. It’s important to remember that there are myriad factors that will influence whether a child experiences anxiety on any given day, including their health, their relationship with others, and how much sleep they’ve gotten. Our job as caregivers is to equip kids with the ability to name their fears, understand that they are not alone, and help themselves through tender nurturing and strong action. Each time we bring resilience resources to a fear, we are placing another stone on the path that leads to freedom.

Wishing you light and love,

Jamie Lynn

Remember, it’s never too late or too early to build your kids’ (and your own) resilience tool kit. There are still a few spots in my upcoming parent-child self-compassion class.

P.S. Here’s a picture of Anjali with her Valentine’s Day card for Grandma 🙂