It’s Summer-Now What!?

So, it’s summer, and my kids are out of school. Yay! Boo! Both things are true.

As a mom who works from home, having kids home for the summer presents both gifts and challenges.

The kids see that I am at home, and they think that they can interrupt whatever I’m doing so that I can tend to them. And sometimes I get grouchy with the kids because I just want to get some work done.

And I tend to feel guilty. I feel guilty when I’m working because I am not attuning to the kids. And I feel guilty when I am tending to the kids because I’m not working. It’s the classic no-win scenario.

Additionally, there are many tasks that I’m not able to complete during the school year (like doing a Kickstarter for my Quest for Self-Compassion Workbooks), and I tell myself that I’ll get around to it during Summer. But during summer, my schedule is all topsy-turvy, and it’s more difficult for me to allocate time to work on projects.

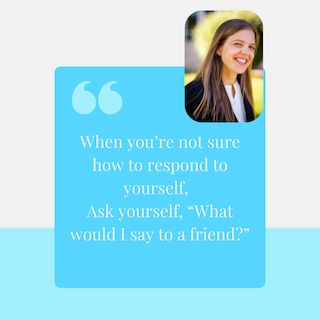

Even though I’m a self-compassion and resilience teacher, sometimes I’m unsure of how to respond to myself when life presents me with imperfect circumstances.

Would you like an awesome tip for what to do when you are unsure of how to respond? Ask yourself, “What would I say to a friend?”

So, here goes: What would I say to a friend who was in my circumstances (this might be you, so I’ll craft my response as if I were talking to you)?

I would tell you…it’s all okay. No matter what you get done or don’t get done this summer, it’s going to be okay.

And summer is for enjoying, so make sure that you take some time to get outside and enjoy the weather—with or without your kids.

And when you feel crazy and like you can’t do it right, that’s because it’s hard. You’re not alone. We all feel a little crazy. And perfection is a myth. You are doing great.

And, I appreciate you. I appreciate all that you do for yourself and your family and the world.

Remember that you matter. Not just for what you do in the world, but because you are a unique and wonderful creation. Be sure to take at least a little time to appreciate your own goodness.

Damn does that feel good to say to you! Now I’m going to read this blog to myself.

Here are the main take-aways for summer with kids:

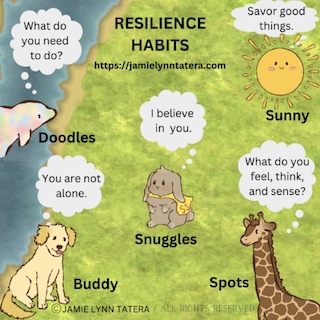

- You are not alone.

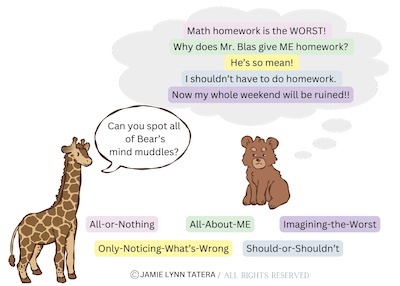

- When you feel overwhelmed, you can think about what you would say to a friend and then say it to yourself.

- You are doing great.

Because I actually have to support myself and my kids financially this summer (it’s true), I should also mention that I have an upcoming parent-child self-compassion class. Here’s a short heart-warming clip of parents and children sharing about their experience with the parent-child self-compassion class.

If you know of anyone who would benefit from taking the parent-child class (for kids ages 7-11 with their caregiver), please let them know. It makes a difference!

Wishing you light and love,

Jamie Lynn

P.S. My daughters performed Carmina Burana with the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra this past weekend. I feel so prateful (proud and grateful) that they had this experience. Full disclosure: they definitely did not get their singing voices from me!