Research suggests that children can learn to think differently about sticky, intrusive thoughts so they don’t feel controlled by them.

Hello Friends!

Mindfulness and self-compassion skills provide a foundation for kids to cope with any mental health challenge. My fabulous research team is currently in the middle of a study focused on how the Parent-Child Mindfulness and Self-Compassion class can help kids with anxiety. In a previous study, we found that kids who took the parent-child program had decreases in depression (and parents had decreases in parenting stress). This is awesome news!

I’ve created the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbooks for Kids to help more kids have access to these resilience resources. The below article is one that I wrote for Greater Good Magazine, and it describes how the skills from the workbook served as a foundation for one child to overcome debilitating OCD symptoms.

Note: You’ll learn more details about how to use the workbook to help kids with tricky feelings in my upcoming Masterclass, which is free for all who order volume 1 of the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbook for Kids on October 24th.

How to Help Kids Deal With Obsessive Thoughts

Research suggests that children can learn to think differently about sticky, intrusive thoughts so they don’t feel controlled by them.

By Jamie Lynn Tatera | September 9, 2024

Rohan’s nighttime fears of being robbed and abducted began at five years old. At nine, Rohan was still sleeping in his mother’s room plagued by nighttime obsessions. “I feel like we’re going to get robbed, and it’s probably real,” Rohan would tell himself. Then he had a second thought that made his fear even worse, “If I believe it too long, it will probably happen.”

This chain of difficult thoughts would lead Rohan to perform nighttime rituals to try to push his fears away. Having repetitive, intrusive thoughts and performing compulsive rituals can be a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Children with OCD can have obsessions, compulsions, or both. (Not all intrusive thoughts point to OCD; children can also have intrusive thoughts that are unrelated to OCD, which can be exacerbated by circumstances such as natural disasters and trauma.)

Trying to suppress the thoughts or distract themselves are strategies that children commonly use when they have intrusive thoughts. It is understandable to want to avoid difficult emotions and thoughts; however, “avoidant” coping strategies like these tend to worsen our emotional and psychological challenges. Ruminating about difficult thoughts can also lead to worse mental health.

If we don’t want to suppress or ruminate on intrusive thoughts, what can we do? Studies have found that the ability to reevaluate difficult thoughts and feelings can lead to better mental health. Understanding our thoughts and feelings and having insight into what is happening in the mind can lead to increased well-being. But just how do we help children, whose prefrontal cortices are still developing, learn to acknowledge, understand, and relate skillfully to sticky thoughts?

We can begin by helping children address less intense thoughts. When Rohan and his mother came to see me for self-compassion lessons, my task was to help Rohan learn resilience habits that he could begin to apply to his everyday mental and emotional challenges. Eventually, these same resilience habits could be applied to more challenging situations, including his nighttime fears. I used the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbooks for Kids that I developed to help Rohan practice mindful awareness, emotional regulation, and self-kindness skills.

Here are some strategies that can help kids build the internal resources to deal skillfully with tricky thoughts.

Non-judgmental awareness through common humanity

My mindfulness and self-compassion workbook has a “Feelings Habit Animal Quiz,” which helps children identify how they commonly deal with emotions: Bear explodes with feelings, beaver obsesses about feelings, chameleon hides feelings, and deer is ashamed of feelings. In taking the quiz, Rohan discovered that his feelings habit animal was a beaver: “Emotions can be sticky for you. Your mind replays situations over and over. A sticky mind can be tricky, but it can also be STRONG.”

By reading about other children in the workbook, Rohan came to understand that lots of kids struggle with difficult emotions, and he wasn’t the only kid with the beaver feelings habit.

Along with identifying that habit, Rohan was introduced to animal characters who represented resilience habits:

- Spots the giraffe spots feelings, thoughts, and sensations.

- Buddy the dog reminds us that we are not alone.

- Snuggles the bunny can soothe us with kind words when we are struggling.

Rohan’s mom attended many sessions with him, and she and Rohan learned resilience habits side by side. His mom was able to appropriately share her own struggles, offer Rohan understanding, and bring increased awareness and connection into their daily lives.

Over time, this combination of playful animals, mindful awareness, and connection to others helped Rohan observe his sticky thoughts with less judgment. He started to talk about his everyday mind glitches with more kindness. When he had difficult thoughts and feelings, he would remind himself that it’s OK to feel this way and that he was not alone.

Building distress tolerance by “sharing the plate”

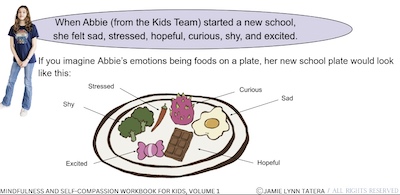

In my work with kids, I encourage them to consider how they can “share the plate” with different feelings about situations, including emotions such as anxiety and curiosity.

Caregivers can help kids understand this idea by using a plate and multicolored crayons. The plate represents awareness, and the crayons represent different emotions. First, the caregiver can introduce the idea by sharing their own experiences with multiple emotions. Then, caregivers can present children with a situation and ask them what feelings they might have. Different-colored crayons can be added to the plate to represent the emotions. Invite children to be curious about big and little feelings, as well as positive and challenging emotions.

In the Mindfulness and Self-Compassion for Children and Caregivers program that I’ve developed, I take this one step further and have children wrap the difficult emotions (crayons) in a washcloth. The washcloth represents the self-compassion habits of Buddy and Snuggles: “Other kids sometimes feel like this. You are not alone. I care about you.”

Once Rohan understood the “share the plate” concept as it related to feelings, we applied this same idea to his thoughts. In addition to his nighttime obsessions, Rohan also had sticky thoughts during the day. We placed a small stuffed animal beaver on a plate to represent his daytime sticky thoughts. Then we added the resilience habit animals Spots, Buddy, and Snuggles to the plate. Spots helped Rohan to observe his beaver thoughts, and Rohan realized that even though he had beaver thoughts, he wasn’t the beaver. This difference between “I have a thought” and “I am a thought” is critical for helping kids to observe the content of their mind.

This exercise also empowered Rohan to understand that he could add other thoughts to the plate, such as reminding himself that he was not alone and offering himself words of encouragement. He could also notice his five senses—what he was seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling, or tasting—or refocus his attention on another activity.

Educate kids

Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Workbook for Kids, Volume 1: 40+ Fun Activities and Comics to Learn to Self-Regulate, Find Peace, and Be Kind to Yourself (Wholly Mindful)

Obsessive-compulsive disorder runs in my family, and my mom, Gwen Tatera, is the author of the delightful children’s book The OCD Beaver. I have a copy of The OCD Beaver on my bookshelf, and during one of our weekly sessions, I invited Rohan and his mother to read the book. Rohan immediately recognized himself in the OCD beaver. He said that he felt less alone, and he had a name for his obsessive thoughts: OCD.

We used the same resilience habits (Spots, Buddy, and Snuggles) to observe Rohan’s nighttime obsessions and rituals. Because I am an educator, not a therapist, I don’t diagnose children. Instead, I took detailed notes on Rohan’s nighttime compulsive rituals, which I shared with Rohan’s school guidance counselor. (If you suspect that your child may have OCD, you can make a list of symptoms to share with your child’s health care provider.) I also helped Rohan understand that robbers don’t usually come when people are home. For individuals experiencing irrational fears, providing knowledge about fact and fiction regarding obsessions can be empowering.

Finally, I introduced Rohan to Jeffrey Schwartz’s four-step method for managing difficult thoughts. Schwartz’s four steps are sometimes used as part of cognitive behavioral therapy programs for individuals with OCD. The four steps help people to recognize, relabel, and reframe their obsessions (in other words, I don’t need to pay attention to these thoughts because they are obsessions, a byproduct of OCD). Individuals then refocus their attention on a different behavior, and over time revalue the obsessions as something that does not warrant their attention or action. Schwartz’s four steps build on a foundation of mindful awareness, which is why I helped Rohan grow resilience habits before introducing him to Schwartz’s four steps.

Over time, Rohan’s internal dialogue moved away from ruminating on his nighttime obsessions and trying to make them “go away,” toward a healthier perspective. Rohan started to relabel and revalue his intrusive nighttime thoughts. When obsessions about being robbed and abducted appeared in his mind, he would remind himself, “I already experienced [these thoughts] for years…and it won’t happen.” Instead of pushing the thoughts away, he would tell himself, “It’s not going to happen. It’s just my OCD thought. OCD is not always right.”

After five years of sleeping in his mother’s room with terrifying fears, Rohan began to sleep in his own room. He discontinued almost all of his nighttime rituals, and his mother bought him a new bedroom set. Rohan and his mother also reported that he felt happier and more confident at school.

Strong and gentle self-compassion

But self-compassion is not just gentle; it is also strong. Toward the end of our sessions, I introduced Rohan to the concept of “Super Snuggles,” which is a strong and encouraging form of kindness. Super Snuggles likes to say, “I believe in you. You can do hard things. You’ve got this.”

Rohan attributed much of his progress to his brain “encouraging him.” And Rohan’s mom was encouraging, as well. She would tell him, “You can beat OCD; you’ve already done so much!” This combination of strong encouragement and gentle acceptance is consistent with the recommendations from the parent-based treatment program for child anxiety, Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions.

When I told Rohan I was going to write this article, I asked him if there was anything he wanted to share. This is what Rohan said: “Even though some people think it’s impossible to beat OCD, some little changes can help make a big change. I know OCD is still in me. But I can beat it.”

If you’re like me, you find this story pretty inspiring. Next week is the launch of the first volume of the workbooks described in this article. Please join me in helping to get these skills to children everywhere!

With joy and hope,

Jamie Lynn

P.S. This past weekend, I went camping with my girls’ Scout troop. It was a side-by-side experience with thirty (loud) kids and 40 degree temps at night. But one of my favorite parts was the candlelight walk on Saturday night, which I actually got to do twice because my daughter lost her phone the first time ;).